How a venture capital fund works

Don't invest unless you're prepared to lose all the money you invest. This is a high-risk investment and you're unlikely to be protected if something goes wrong. Take 2 mins to see our risk warning.

Ibrahim Khan

Founding Partner

December 21, 2022 | 27 min read

Many of you will know that we run a venture capital fund over at Cur8 Capital, and even more of you will have heard about venture or “VC” investing in passing over recent years.

The eye-catching 6000x returns made by early investors in recently IPO’ed tech companies will have, well, caught your eye.

But what on earth is VC investing?

Well, the answer is surprisingly complex.

I used to be a funds formation lawyer at a specialist law firms that dealt with private market funds and I’ll be using both my legal experience as well as my Cur8 Capital experience to inform the analysis. In this article I’ll be explaining:

Venture capital is at heart money you are willing to lose all of, in the hope of making a massive return.

Your typical VC investment will be very early in a company’s journey and usually before material revenues are achieved. Early stage investors (like me) will often invest in just a team and an idea or at the prototype stage.

VC can be contrasted to private equity. Private equity funds typically invest much larger amounts into mature companies and usually involve debt financing too. A typical PE fund investment would be something like £25m equity, £75m debt, to acquire a majority stake in a £120m company.

A typical VC investment on the other hand might be a £1m investment into a £4m company with no debt.

VC can also be contrasted with public markets, i.e. the stock exchange. VC is very much investing in unlisted, smaller, private companies. This means that exits are much harder to achieve and there are much longer time horizons on the investments.

VC investing might sound like a big gamble based on the above description, however there is a reason why so many pension funds and large, boring institutions invest in this asset class.

The secret is that, with effective portfolio construction, you can mitigate significantly the downside, whilst maintaining most of the upside.

Your chances of finding a unicorn are either 3 out of 5 million[1] (0.00006%) or 1 in 40[2] (2.5%). Your chances of finding a unicorn if you invest in any old random company are 0.00006%, while your chances dramatically improve if you invest in venture fund backed companies.

In other words, if you invest alongside the pros you dramatically increase your chances.

But even then, your luck isn’t looking amazing at 1 in 40. So how do you mitigate this?

Well the answer lies in understanding that some further stats J.

VC investing is all about “home runs”. Getting into the winners is all that matters because the winners are so massive. That is VC investing in a nutshell.

As you can see from the data below, pulled together after analysing thousands of deals, the deals that return you at least 10x your initial investment amount to around 4%.

Most of your investments will therefore either go to zero or make a negligible return after a 5-10 year period (because that’s how long it would typically take a young company to get anywhere).

So if you invested £1000 into venture, and you only invested in 1 company, you would be incredibly foolhardy as your chances of hitting upon a winner are pretty slim. The most likely outcome is that you would lose most of that money.

But if you invested that £1000 in a number of VC investments alongside other professional VC investors then you dramatically increase your chances. With a portfolio of 25 investments you would make it quite likely that you have invested in at least one 10x or more company.

Let’s model this out. Assume that 24 of your companies return you 3x your money, and only 1 returns you 20x.

As you can see, your overall portfolio would be worth £3680, a healthy 3.68x return. But without that outlier it would be a pretty average return. You’d probably do equally well just investing in stocks in the stock market – and that is much safer and far more liquid (you can easily sell out).

Now increasing your hit rate of wins to 3 out of 25:

Suddenly your overall portfolio is now worth £5040, or a 5x return.

Let’s say one of your investments hits 1000x, this is what the portfolio now looks like:

Now you return £8240 or 8.24x your total portfolio.

And, by the way, those crazy numbers do actually happen. Early investors in Facebook, Coinbase, Apple, Tesla, etc. all made those numbers or even better.

The name of the game is clear: Get into the winners and optimise your investment to do that.

You do this most effectively by either being a senior tech person yourself, so you constantly get access to top deals, or you should align yourself with a top VC fund or VC syndicate that gets access to those deals for you.

You can split up VC investing into angel investing, corporate VC investing or VC fund investing.

Angel investing is done by individuals, corporate VC investing is done by corporates (i.e. by taking minority stakes in other companies) and VC fund investing is done by professional VC fund managers.

For the purposes of this article we are zoned in on the fund bit.

Within the VC fund world, you get a wide variety of fund types that vary on the basis of:

Getting into the best deals is about knowing the right people and really deeply understanding a market. That’s why geographic focus and proximity are a relevant strategy for many VC funds.

Industry focus too is all about leveraging a fund manager’s expert insider knowledge about the best startups to invest in as well as his access into the best deals. (Founders like experts to invest in their companies because of the value-add they bring).

Both geographic and industry focus are about increasing your odds and playing to your strengths to get into the best deals.

Stage of investment however is all about risk management and size of investment. During its lifetime a company will go through many funding rounds. They are usually called:

The cheque size into a deal at pre-seed might be £100k, at seed it might be £1m, at series A it might be £5m and at Series B onwards you’re looking at £10-100m.

As we discussed earlier, a VC fund wants to make about 25 similar-looking investments, ideally with a 5-7% ownership stake in a company with each investment in order to give itself a good chance of getting into outlier investments and having sufficient exposure for it to be worthwhile.

That means a typical early stage fund could be just £20m while a typical Series B/C fund would probably need to be £500m.

Early and late stage investing therefore are completely different beasts, done by different funds, requiring different skillsets and attracting different investors.

Your typical early-stage fund would attract investment from affluent individual investors and smaller institutions. Your typical later stage or “growth stage” fund – as it needs to raise so much more – would attract larger institutions looking to deploy £25-50m cheques at a time.

A typical VC fund is optimised for the following:

Contrary to what many people would think, the reason most larger VC funds are structured offshore is not to avoid tax, but to make sure that investors are not double-taxed.

Let’s say you have certain investors who are tax-exempt (e.g. pension funds or charities). They don’t want to pay any tax at all ideally. So if you establish your fund in a country where there is taxation, the profit first get taxed at the fund level, and then get passed on to you.

Now instead if you are based in a tax-free jurisdiction, then the money gets passed to you without being taxed. This doesn’t mean you avoid tax completely – you are still responsible for your own tax affairs in your own country.

The other big benefit of structuring a VC fund in overseas jurisdictions is that it allows for anonymity. Larger institutions are very reluctant to be publicly associated with any investment for fear of PR backlash. A case in point is the Queen’s tiny investment into a Harbourvest private equity fund which caused a furore.

Typically, the structures also allow for limited liability as well, so both the fund manager and the investors cannot be legally chased in case something goes wrong at the investment level, e.g. if a company creates a dangerous product and then gets sued for it.

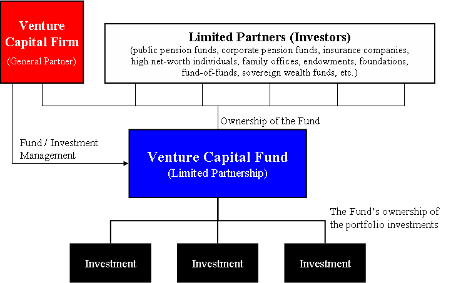

The typical fund structure is a limited partnership structure, also sometimes referred to as a GP-LP structure.

Here is a typical example:

Setting it up this way allows for the fund to have its own legal entity – which is important as it then allows for the fund to directly transact with investee companies, investors, and the fund manager (referred to as the “General Partner” or “GP”).

The relationship is governed by a Limited Partnership Agreement which sets out the basis on which the fund will operate. These are extremely detailed documents that typically run to over 100 pages long.

There is an annual management fee, usually of around 1.5-2.5% of the fund size. For example, a £100m with 2% management fee would pay the fund manager £2m annually.

All other economics are distributed according to a tightly negotiated and drafted set of terms called the “waterfall”. Here is a typical example:

The LP here is the investor and the GP is the fund manager.

The GP equity portion is the small amount of money the fund manager has to invest in the fund itself. Investors usually demand this in order to ensure that incentives are aligned with the fund manager.

The big idea here is that the investors should get their capital back first before the fund manager gets any profits, then the profits should be given at a preferential rate to the investors for a set amount, and then after that the profits should be split between the fund manager and the investors at the agree 80/20 arrangement.

The preferred return is the bit after the initial capital has been return. It is usually set at 6-8%.

Practically, it means that, for an investment with £300 profit on an initial investment of £100, an investor gets back £100 first. Then the investor gets the first £8 of profit. After that, the rest of the profits are distributed such that ultimately the fund manager and the investors end up with £60 and £240 respectively.

There is a slightly complicated thing called the GP catch up. Remember that because of preferred return the investor got all the profits initially (up to £8)? Well, once the £8 has been hit, the fund manager can now start getting his payment. But right now he is down £1.60 (20% of £8). So first he gets all the profits until he is “caught up” and then after that all profits are split 80/20.

The entire economic structure of a VC fund is set up to incentivise fund managers to generate profits, and to protect investors’ original investment as much as possible.

In the UK there is a tax-scheme called the Enterprise Investment Scheme which comes with some significant tax advantages. Startups that are eligible for “EIS” money come with:

Because of these perks, early-stage and angel investing in the UK is driven primarily by EIS considerations.

There is a problem however. Your typical VC fund is structured in a way that would make investors unable to benefit from EIS on their investment.

The reason is because EIS is an individual investor benefit, not a company investor benefit. So individuals have to invest personally, not via any limited company or partnership.

But a typical VC fund is structured as a partnership with its own entity (to limit liability as we discussed).

Enter EIS funds.

EIS funds deploy a different type of legal structure in order to achieve the same pooling effect of a VC fund.

Instead of using a partnership structure (which itself has a legal personality) you use multiple parallel segregated managed accounts. In effect what you are doing is managing several separate investor portfolios in tandem, but you have agreed with all investors that you will invest according to a specific, set strategy.

This approach makes the investment EIS-eligible because now the beneficial investor is the investor – with the EIS fund vehicle acting simply as a “bare trust” or a look-through vehicle. This means that HMRC will pay out on the tax rebate applications from each investor.

Win.

This different investment structure also enables certain other benefits.

First, as each investor has their own segregated account, you can effectively top up your investment whenever you like. With a typical VC fund you would all have to close your investment and invest at the same time.

This allows a VC fund to be “evergreen” or a “rolling fund”, i.e. an entity that can continuously be topped up and continue to deploy.

This approach also means that different investors will end up with slightly different portfolios based on the time they invested.

EIS funds also typically have a lower entry investment amount as they are designed to cater for individuals, not just institutions.

EIS funds will typically also vary their economic structures – usually for the worse, though sometimes for the better too.

You will see annual management fees of up to 3%, but then you will also see fees capped at 12-14%, rather than the 20% that is normal in a VC Fund. (This capping idea is something we’ve used at our own EIS fund at Cur8.Capital.

The reason for these varied economics are usually:

There are 3 primary ways you can invest into a venture capital fund.

Angellist is the largest venture syndicate platform in the USA and globally. They also allow fund managers to host their fund on the Angellist platform and allow accredited investors to invest with them. A recent innovation is the rolling fund – which is exactly what it sounds like. The idea is that you subscribe for new quarterly mini-funds and the fund manager keeps deploying that into new investments.

The positives of this are that:

The downsides of the Angellist route are that:

You can also directly invest into the institutional VC funds. However the problem here is getting access and having sufficient capital. Your typical VC Fund has an entry ticket of at least £250k, which only makes sense if your total net worth is north of £5m.

The other big problem is getting access. You will appreciate that a VC fund raising £100m is going to focus on the £10-50m sized tickets, rather than your £250k. So the only £250k cheques they will accept are from friends and family or from value-add investors who they want to help their portfolio once it is up and running.

EIS funds are rather like Angellist funds in that you get the benefit of rolling commitments, smaller entry tickets (typically around £10-20k), and usually the investment process is pretty self-serve once you get onto the fund manager’s website. A few forms to fill in and voila! You’re ready to invest.

The other big benefit for UK investors with the EIS fund route is that you can claim all the lovely tax rebates you want to. That doesn’t mean that overseas investors cannot invest in an EIS fund, just that they won’t benefit from the UK tax-specific stuff.

The downside to an EIS fund is that these are usually smaller funds (£10-30m) and you typically wouldn’t expect a larger institution to have co-invested with you. This means that, unlike an institutional VC fund, you don’t get that additional comfort of a big ticket investor looking after investor interests at the advisory committee.

Sidebar: advisory committees are what they sound like. They usually only have limited powers and those become most relevant when things go badly wrong. In the good times they meet regularly throughout the year and provide oversight into the fund’s work. Advisory committees cost time and money and so they only make sense for larger funds typically where it makes sense for an investor and fund manager to do the work needed for an advisory committee.

There are now a number of venture funds across the world focused on social impact, investment into overlooked communities, and looking to reduce inequality. These include Impact X, Harlem Ventures, Ada Ventures, and the British Business Bank’s regional programmes.

On the sharia-compliant VC fund side however there are not very many that are live. Cur8 Capital’s inaugural EIS fund is the first explicitly sharia-compliant venture fund in the UK. Internationally there are now efforts to raise sharia-compliant funds however they have not yet launched.

The key considerations that make a fund sharia compliant include:

These matters are very difficult to deal with once a fund is live and has been designed for non-sharia-sensitive investors.

Venture investing is a high risk, high reward pursuit when done right. But by investing in a VC fund you can significantly derisk your investment by pooling – and if you’re in the UK you get to reduce your tax burden significantly too.

For those looking to invest in a fund, check out Cur8 Capital’s new EIS Fund. For institutional investors, Cur8 Capital is also raising a fund. Drop us a line via email to team[@]cur8.capital.

[1] https://republic.com/blog/investor-education/unicorns-are-the-rarest-startups-around

[2] https://www.angellist.com/blog/angellist-unicorn-rate

[3] https://www.toptal.com/finance/venture-capital-consultants/venture-capital-portfolio-strategy

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Venture_Capital_Fund_Diagram.png

[5] https://www.pefservices.com/distribution-waterfalls-101/

[6] Assuming a 45% tax band